The Librettist And Director of Blue

In a conversation over Zoom, Seattle Opera writer Glenn Hare and Tazewell Thompson talk about the characters he created in Blue, Tazewell’s childhood, and how he came to love opera—especially operas about nuns.

Tazewell Thompson is the 2020 Music Critics Association of North America award recipient for Best New Opera in North America for Blue. The New York Times and Washington Post both noted the opera as a Best in Classical Music 2019. He has over 150 directing credits, including 30 world and American premieres, in opera houses and theaters in the US, France, Spain, Italy, Africa, Japan, and Canada. He earned an EMMY Award nomination for Best Direction and Best Classical Production for Porgy and Bess Live from Lincoln Center. At Seattle Opera Thompson serves as a coach/mentor in the Jane Lang Davis Creation Lab for up-and-coming Washington State librettists and composers. He was also a panelist on the 2018 community forum, Breaking Glass: Hyperlinking Opera & Issues, a national collaboration with Glimmerglass Festival. Blue is his Seattle Opera directorial debut.

Glenn Hare: To start, how much does Blue reflect your own life?

Tazewell Thompson: Well, none of it really is my story. I did not grow up with a family like the one in Blue—a mother and father all together. A unit. Not at all. At a very early age, because both my mother and my father had problems, my parents and I were separated. I was left alone, or I was sent to live with their friends. I was sometimes placed in foster residences.

My grandmother, my father's mother, stepped in and placed me in a Catholic convent. I was there for eight years. The nuns were my family. They took care of me and recognized my artistic talents. They noticed that I loved to read. They noticed that I quickly learned to read and write Latin. I could speak Latin also because I was an altar boy. As for the foundations that parents give, I received that from the nuns.

The family in Blue, I would say, is the family I wish I had, one where the father is extraordinarily responsible. The mother is talented, ambitious, and successful. I see this family here in Harlem where I live. Black entrepreneurs—owners of little variety stores, restaurants, barbershops and beauty parlors, street vendors, municipal workers, some black police officers, like the ones I interviewed while writing Blue.

|

|

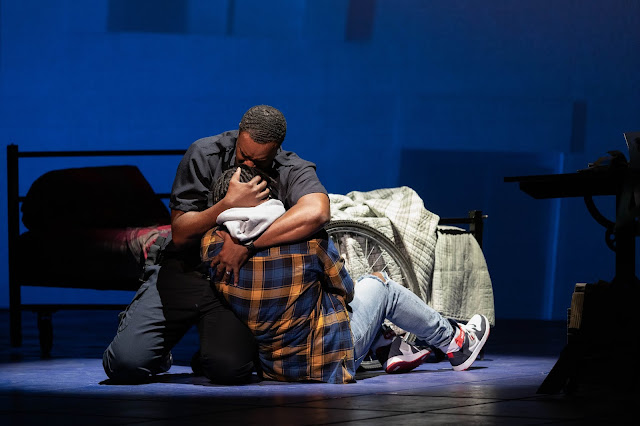

Kenneth Kellogg (The Father), Briana Hunter (The Mother), and Aaron Crouch (The Son) in Blue. Credit: Karli Cadel / Glimmerglass |

Tazewell Thompson: I did not want to write about a family that was struggling. There has been enough of Black struggle and dysfunction on the screen and stage: absent fathers and desperate single mothers barely surviving. I wanted to show a positive household moving forward. In Blue, The Mother is educated and talented with equally talented and educated girlfriends. Surrounding The Father, a police officer, are his best friends, fellow police officers, men who are responsible, wonderful, aspiring fathers to their children.

Glenn Hare: I would like to talk about a few scenes from the opera. The first one that struck me as powerful takes place between The Father and The Son. The father-son tension is true to life and universal.

Tazewell Thompson: I think so. Two men, Black men—one very young man, not quite 18, and then, of course, the dad. They are fighting for territory, trying to claim a dominant place in each other's life, in each other's heart. Parents and teenagers will recognize this scene because it happens in every home to some degree.

One of the New York City Police officers I interviewed has two teenage kids. The daughter runs to the door when he comes home. She throws herself in his arms. She adores her father. The son, on the other hand, goes to his room and closes the door. He is appalled that his father is the “Man in Blue,” representing “the oppressor,” wearing the clothes of the enemy. The police officer asked me, ‘Do you think he'll grow out of it?’ I said, ‘Oh yes, he will. He'll understand.’

The Son in Blue is a typical teenager in the sense that no older person—certainly at least twice as old—can possibly know anything about the world, or what he, the teenager, is experiencing. What does this “old man” know? The Father doesn't quite know what all the kids are up to. However, he certainly knows a bit more about life than The Son. In time, The Son will come to understand what The Father is trying to do. The Son might say, ‘My father really got it. He loves me.’ Sadly, he never has that opportunity.

Glenn Hare: The next scene that

struck me as both poignant and funny is the “Do’s and Don’ts” talk. In African

American families, the conversation is widely known as “The Talk.” I’m not

talking about the birds and the bees here. The Talk starts with ‘If you

encounter the police, make sure you have all your credentials, be respectful,

and keep your hands in sight…’

Kenneth Kellogg (The Father) and Aaron Crouch (The Son) in Blue. Credit: Karli Cadel / Glimmerglass

Tazewell Thompson: ‘...Don’t run across the street. Walk. Don’t walk. Don’t wear a hoodie. Don’t wear your ball cap backwards. Don’t pierce your ears. Don’t get a tattoo. Don’t wear sunglasses. Don’t look “the man” in eye. Look “the man” in the eye. Have a photo ID. Voter registration. Library card. Passport. Skate key. Dog tags. Walk. Don’t walk. It is absurd. I wanted to bring out the absurdity that Black parents should even have to have a talk like that in the first place. Where are we? Are we in apartheid South Africa? Can we not just walk down the street without being confronted just for being who we are, Black men and women?

Glenn Hare: You took the conversation to an entirely new level. Like I said, this scene is both poignant and funny.

Glenn Hare: How difficult or easy is it for you to direct the libretto you wrote?

Tazewell Thompson: I am having the time of my life. It is not difficult for me at all. I am in a very unusual position, circumstance. I love it because I know the people in Blue. I know the women. I know the men. Not because I know these characters personally, but because I created them. I recognize them from my neighborhood. I witness them working, gossiping, joking, talking, and arguing over important issues, and living their lives. I also know the kind of family that I wish I had as a child. I love that I am directing the Seattle Opera production.

Glenn Hare: I want to jump back just a moment. You have talked about being raised in a convent. I read that the nuns played opera in class. Do you recall the first live opera performance you saw?

Tazewell Thompson: The first opera I saw was Dialogues of the Carmelites, of all things.

Glenn Hare: Yes, more nuns.

Tazewell Thompson: Dialogues of the Carmelites remains my favorite opera. The libretto, inspired by a true story, has real human beings, not pasteboard characters, or mythological creatures. I love it all: the assertive orchestrations; the abundant fund of sensuous melody; the perfect choice of harmony for vocal expression; the stretches of recitatives and parlando; music that is spare, precise, subtle, nuanced, gut-wrenching; themes of pride, fear, faith, courage, community. “The “Salve Regina” at the end of the opera still emotionally affects me as I recall it even now. Nuns. I directed my own production at Glimmerglass, New York City Opera, Vancouver, and Indianapolis. It is a great work. A beautiful work. A major work.

Tazewell Thompson's production of Dialogues of the Carmelites. Credit: George Mott / Glimmerglass

Glenn Hare: Now more than ever

before, there are more stories about the Black experience on opera stages. From

your perspective, why?

Tazewell Thompson: You are right, even more so than 2019.That was the year The Central Park Five (Long Beach Opera), Fire Shut Up In My Bones (Opera Theatre of Saint Louis), and Blue (Glimmerglass Festival) premiered. Now, it is happening because opera and theater companies are looking to support all things Black. Companies are finding it necessary to demonstrate their commitment to diversity and inclusion. Perhaps they are discovering that they have not given much attention to these stories. At this time of “enlightenment,” of “woke-ness,” companies are realizing, besides and beyond Porgy and Bess, that they haven’t done much at all. I love Porgy and Bess. I’m directing a new production at Des Moines Opera in June. However, there are so many more stories opera companies should be paying attention to. For whatever reason more companies will be doing Black productions. I hope so. Finally. About time. I remain hopeful that companies will continue to find stories that are written by Black composers and librettists, or stories that involve Black artists on stage, or doing things that are extraordinarily brilliant, like a multicultural staging of a classic title. It is good that there is this explosion now. It will lead to good things for everyone—the audience and the artists.

|

| The Central Park Five. Credit: Long Beach Opera |

Glenn Hare: This is my last

question: In the first scene, one of the girlfriends mentions a pot of collard

greens and ham hocks. Is Blue the first libretto to talk about greens

and ham hocks? I think it is.Fire Shut Up In My Bones. Credit: Eric Woolsey / Opera Theatre of Saint Louis

Tazewell Thompson: It probably is. Towards the end of the opera,

The Mother mentions all kinds of soul food she is preparing for The Father and

The Son. Six types of greens, including collards. The Girlfriend says, to The

Mother to be, as a wish for the child to be born: “l wish, not a pot of gold

but a pot of greens with a ham hock on the bottom, remind you of who you are,

where you come from, and how far you will go.’ I think you are probably right,

Glenn. Blue could be the first opera to mention collard greens and ham

hocks and I love it. Thank you, Glenn. I

love that you recognized it.

Mia Athey (Girlfriend 3), Brea Renetta Marshall (Girlfriend 2), Briana Hunter (The Mother), and Ariana Wehr (Girlfriend 1) in Blue. Credit: Karli Cadel / Glimmerglass

No comments:

Post a Comment