The Golden Age

By Naomi André, Ph.D.

|

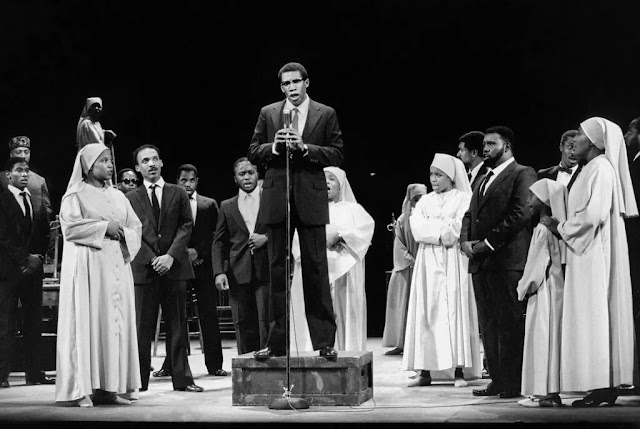

| Will Liverman as Charles M. Blow in The Metropolitan Opera's premiere of Fire Shut Up in My Bones by Terence Blanchard |

Naomi André is a professor at the University of Michigan, where her teaching and research focuses on opera and issues of surrounding gender, voice, and race. Her writings include topics on Italian opera, Schoenberg, women composers, and teaching opera in prisons. Her publications include Black Opera: History, Power, Engagement and co-editor of African Performance Arts and Political Acts (2021). She has served as Seattle Opera’s Scholar-in-Residence since 2019.

Today we are in a golden age of Black Opera. Black participation in American opera goes back to the antebellum period. But two big shifts happened in the late twentieth century, making possible this current “Golden Age”: first, the success of Black singers in major roles at leading opera houses; and secondly, new operas centering on Black experiences and told from the perspectives of a Black (or interracial) composer-librettist team.

Crossing the Color Line

Marian Anderson’s historic debut at the Metropolitan Opera on January 7, 1955, as Ulrica in Giuseppe Verdi’s Un ballo in maschera is considered the symbolic desegregation of opera as a genre. But she was not the first Black singer to appear at a white opera company. A few African American singers were able to create limited opera careers in Europe, including Lillian Evanti (1890–1967, born Annie Wilson Lillian Evans in Washington, DC), Florence Cole Talbert (1890–1961, born Florence Cole in Detroit, MI), and Caterina Jarboro (c. 1903–1986, born Kathrine Lee Yarborough in Wilmington, NC). In 1925 Evanti sang the leading roles in Lakmé and La traviata in France and Italy, Talbert sang Aida in 1927 in Italy (probably the first Black singer to perform this role in Europe), and in the early 1930s Jarboro sang her signature title roles in Aida and L’Africaine in Italy, France, and Belgium.

In the United States, near the Metropolitan Opera was a smaller, more experimental company that had a greater focus on promoting young American singers and composers. Founded in 1943 (sixty years after the Metropolitan Opera), New York City Opera (NYCO) presented Todd Duncan as Tonio in Pagliacci in 1945, ten years after he created the role of Porgy in Gershwin’s Porgy and Bess. Also, in this decade before Anderson sang at the Metropolitan Opera, Camilla Williams sang the title role of Madama Butterfly at NYCO in 1946.

|

| Lillian Evanti, soprano, studied and performed in Europe. |

Black Voices

The first generation of Black singers after Marian Anderson who made it onto major opera stages has been better documented than the earlier generations. The bright star of the Metropolitan Opera after Anderson’s debut was Leontyne Price, who regularly appeared on that stage for nearly twenty-five years and had a major career in the US as well as internationally. Martina Arroyo, Shirley Verrett, Grace Bumbry, Leona Mitchell, Florence Quivar, Kathleen Battle, Jessye Norman, Barbara Hendricks, Hilda Harris, and Harolyn Blackwell, are personal favorites whom I was fortunate to hear during my time in New York City during the 1980s.

|

| Left: A young Leontyne Price photographed in 1952. Right: Baritone Robert McFerrin made his Metropolitan Opera debut twenty days after Marian Anderson in 1955. |

The list of Black male singers who made it to the top is unfortunately shorter than the women—not because they were less talented, but because of a racialized fear of Black men in American culture (especially in the aftermath of Jim Crow) and anxiety about seeing interracial relationships between Black men and white women on stage. Robert McFerrin made his debut at the Metropolitan Opera twenty days after Marian Anderson in the role of Amonasro (January 27, 1955). (As the character is a widower, the Met could avoid the issue of casting a love interest for him.) Roland Hayes, Paul Robeson, Jules Bledsoe, William Warfield, and many other Black men had voices that would have soared in opera houses, had there been the opportunity. George Shirley, Simon Estes, Willard White, Terry Cook, and Vinson Cole are among the earliest generation of Black men who were able to have careers in international operatic venues. Our current generation enjoys a wealth of Black women and men singing opera, though opportunities for men are still fewer than those for women. Moreover, there are still barriers for Black singers as well as giant hurdles for other singers of color that keep them from having a true representation of the best voices out there.

While Black singers have been performing in opera for over sixty years, the representation of narratives and subjects has lagged behind. Porgy and Bess, fraught for its negative stereotypes yet ever-popular thanks to its beloved music, has provided important opportunities for Black singers to portray Black characters, instead of appearing (due to “colorblind” casting) primarily as European characters in non-Black plots. Since the end of the twentieth century, and gaining speed up to the present, opera companies have begun to program operas written by Black and interracial composer-librettist teams about Black experiences that break free from negative stereotypes.

|

Black Creators

In 1949 New York City Opera made history with the premiere of William Grant Still’s Troubled Island (about the Haitian Revolution), which was the first opera by a Black composer performed by a major company. Yet despite the strong performances in Troubled Island and Still’s prolific output (he wrote eight operas), other theaters have been slow to follow suit. A new age could be said to have started in 1986 with the world premiere of Anthony Davis’s X, The Life and Times of Malcolm X at NYCO. Of the current Black composers of opera, Davis is the most prolific. His eight operas have been presented by major opera companies: Lyric Opera of Chicago, Opera Theatre of St. Louis, Omaha Opera, Long Beach Opera. The Central Park Five, which he composed in 2019 to a libretto by Richard Wesley, was the first Black opera to win the Pulitzer Prize in Music.

|

| Long Beach Opera premiered Anthony Davis's jazz-infused new work, The Central Park Five, in 2019. |

Seattle Opera is part of this contemporary push to present more operas about Black experiences as well as stories of other People of Color. In March 2020 they gave the West Coast premiere of Charlie Parker’s Yardbird, a 2015 opera by composer Daniel Schnyder, to a libretto by Bridgette A. Wimberly, inspired by the jazz bebop great. Now SO presents another West Coast premiere: Jeanine Tesori and Tazewell Thompson’s Blue. This drive for greater diversity in opera subjects continues next season, with the commission and world premiere of A Thousand Splendid Suns. Based on Khaled Hosseini’s award-winning 2007 novel, this opera about life in Afghanistan will be directed by Afghan filmmaker Roya Sadat.

Blue belongs to a trio of ground-breaking operas first heard in the summer of 2019. The Central Park Five, by Anthony Davis, won the Pulitzer. Terence Blanchard’s Fire Shut Up in My Bones went on to be the first opera by a Black composer presented at the Met. Blue has already won a major award (Best New Opera from the Music Critics Association of North America, 2020); a CD recording is to be released in 2022. It comes to Seattle from its Glimmerglass Opera premiere (July 2019) and the September 2021 production by the Michigan Opera Theatre. After Seattle, Blue heads off for performances at other opera companies including Washington National Opera, Toledo Opera, and Pittsburgh Opera.

|

| Composer and trumpet player Terence Blanchard's opera Fire Shut Up in My Bones in 2021 became the first opera by a Black composer presented at the Met. |

Art Imitates Life

While many operas about Black experiences are based on historical events and famous people, Blue takes a different approach. The characters are not named individually, but by relationship titles (e.g., Mother, Father, Son, Reverend, Girlfriend, Police Buddy) which outline the intimate connections among this close-knit Harlem community. These characters can stand in for any community that has lived through the universality of trauma, even as each experience is unique and individual to Black Americans. The opera concerns the love and humanity in a young Black family and the tragic loss of their teenage son. It captures the pain experienced by too many families and communities that have lost unarmed victims to systemic over-policing. In an uncanny way Blue, premiered in 2019, anticipated the agony of the 2020 summer, when three highly publicized victims—Ahmaud Arbery, Breonna Taylor, and George Floyd—became the specific names representing the increasingly visible violence against Black and Brown people.

Watching Blue together now in 2022 takes us on a journey through a new story in opera, one we can both enjoy and grapple with as we re-form the audience community we have deeply missed during the pandemic. Blue humanizes the numbers and offers the space and opportunity to remember those we have lost while also sharing in the celebration of their lives.

|

| Tazewell Thompson and Jeanine Tesori's opera Blue won the 2020 award for Best New Opera from the Music Critics Association of North America. |

No comments:

Post a Comment